Huntington disease and the potential of gene silencing

Will genomic therapy be the key to treating one of the UK’s most devastating degenerative diseases?

In the UK, 12 in every 100,000 people have Huntington disease. This incurable neurodegenerative condition affects movement and cognitive function, and can also lead to changes in behaviour and personality. The loss of mental and physical faculties gets progressively worse, and life expectancy is drastically reduced – sometimes to just 10 years from the time of diagnosis. Currently available medication can treat some of the symptoms, but cannot slow or prevent the inevitable deterioration of the brain.

The root cause of Huntington disease

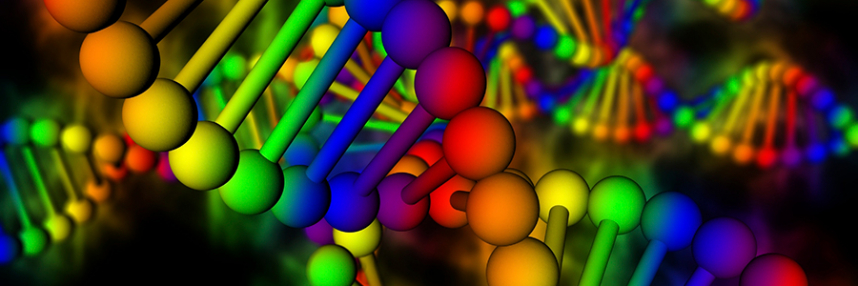

It has been known for years that the huntingtin protein is responsible for Huntington disease. Sufferers have a faulty huntingtin (HTT) gene with a DNA sequence variation known as a CAG repeat. In most people the CAG segment in the HTT gene is repeated 10-35 times, but when a greater number of repeats is present a larger form of huntingtin protein results. People with 40 or more CAG repeats almost always go on to develop the disease.

Exactly how the larger protein causes the disease is not yet fully understood, although a new study may point the way; research in fruit flies shows that HTT controls the movement of vital components of neurons, the cells that form the core of the nervous system.

Genomic potential

It is hoped that a newly developed ‘gene silencing’ therapy called ISIS-HTT could become the first treatment to correct the underlying defect that causes Huntington disease. Gene silencers use a method known as RNA interference to alter the production of specific proteins – in this case, huntingtin protein. The activation or ‘expression’ of genes to produce proteins is mediated via a molecule called messenger RNA (mRNA), which carries the protein making instructions from the DNA to the cell’s protein-making factories. Gene silencers are complementary, mirror-image molecules that bind strongly to specific mRNAs, blocking production of the corresponding protein.

Pre-clinical trials have shown that lowering the production of the abnormal huntingtin protein in this manner allows animals to recover significant motor function. Now 32 patients are taking part in the first human trial at University College London, during which they will receive monthly spinal cord injections of increasing doses of ISI-HTT. Scientists hope to discover whether the treatment is safe, and explore the effects it may have on huntingtin protein levels – and therefore on disease.

Cath Stanley, the chief executive of the Huntington’s Disease Association, told the BBC: “This is the first potential major breakthrough in terms of delaying symptoms of Huntington’s disease, it’s such an exciting step forward.”

The significance of success

Whilst these are very early days, and no-one yet knows how effective the gene silencing treatment will be, the trial represents an important transitional step towards an era of genomic medicine – where innovative treatments are developed based on an in-depth understanding of how the genome functions in health and disease. If it proves possible to halt or even slow the progress of this devastating inherited condition, then the speed at which genomics is transforming areas of medicine will become even more apparent.

–