Birth of world’s first gene-edited babies sparks outcry

Why is the procedure so controversial, what are the risks, and could it ever happen in the UK? We take a look at the key issues

Twin girls, born last month, are the first people to be born from genome-edited human embryos, Chinese researchers have announced.

The news sparked criticism from researchers across the world, but why? And could this procedure ever happen in the UK? Amid the widespread condemnation and some sensational headlines, here is what you need to know.

What did the researchers do?

Dr He Jiankui, an associate professor at the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen, and his colleagues used CRISPR/Cas9 to edit a gene called CCR5 from human embryos with the goal of producing ‘HIV-resistant infants’.

CCR5 codes for a protein that HIV hijacks to enter and infect a white blood cell. Individuals who are naturally HIV-resistant have been found to have variants of this gene.

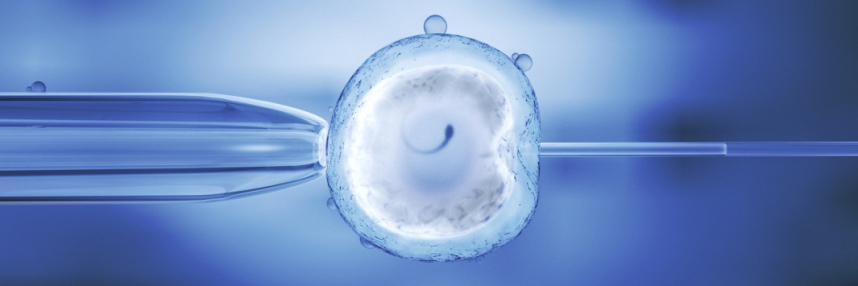

The embryos were all from seven couples undergoing IVF, where the male partner had HIV and the female partner was HIV-negative.

The genome editing components were introduced at the time the embryos were created. After five days’ growth, cells were removed from each embryo and tested, to see if the target gene was successfully edited.

Dr He explained that 16 embryos were edited and 11 were transferred before the twin pregnancy was achieved. According to Dr He, another woman in the study is pregnant, but still at a very early stage.

In one of the twins, both copies of the CCR5 gene were successfully edited, and the other girl twin has only one edited copy, which may confer some benefit should she become infected in future, but is unlikely to confer resistance.

Why has this work been criticised?

First, the consensus among the scientific community is that, although extremely promising, CRISPR/Cas9 editing in human embryos is not yet perfected, and more research improving safety and efficacy needs to be done before it is used to establish pregnancies.

Dr Kathy Niakan of the Francis Crick Institute in London said in a statement: “Given the significant doubts about safety, including the potential for unintended harmful side-effects, it is simply far too premature to attempt this.” Dr Niakan uses CRISPR/Cas9 to edit human embryos as part of her research.

The second reason is that the embryos that became the twins were already healthy. If, in future, there is consensus that genome editing is safe enough to use clinically, the general expectation had been that it would be used on embryos carrying gene variants that cause severe, life-limiting conditions.

Although the twin’s father is HIV positive, he (and all the men in the trial) is using antiretroviral therapy, which makes his risk of transmitting the disease negligible. The twin girls are at no greater risk of acquiring HIV than anyone in the general population. Furthermore, HIV treatment options are very good and, in countries where antiretroviral therapy is available, people living with HIV can thrive.

Additionally, while the edits made to CCR5 can confer resistance to HIV, not all strains of HIV use the protein produced by CCR5 to infect cells. Some strains use a different protein, so these twins will not have any resistance to these strains.

The CRISPR/Cas9 technology used is relatively widespread and easy to use, so many scientists do not doubt that the twins have had their genomes edited. However, this work has yet to be verified and published in a peer-reviewed journal.

The organising committee of the Second International Summit on Human Genome Editing said in a statement that, if shown safe in future, genome editing could be acceptable, but criteria would include “a compelling medical need, an absence of reasonable alternatives”, neither of which would apply in this case.

Could this happen in the UK?

Not currently. It would require parliament to change the law before it would be legal to allow a genome-edited embryo to grow into a baby.

Human embryos can be edited in research, but they cannot be kept longer than 14 days and the researcher must have obtained a special licence from the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority.

According to the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Acts 1990 and 2008, it is illegal to transfer an embryo that has been genetically changed in any way (except mitochondrial donation) into a woman’s uterus.

–