Human gene editing: where do we draw the line?

Advancements in our ability to alter the human genome have sparked fresh debate over ‘designer babies’ and health ethics

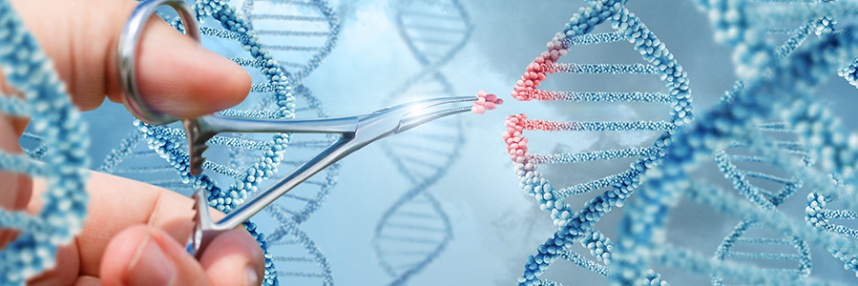

Renowned scientists, ethicists, and quite a few reporters, met in Washington DC earlier this month for an international conference to discuss the hot topic of human gene editing. Remarkable new techniques now allow precise insertion, deletion or alteration of DNA sequences, more often than not using the CRISPR-Cas9 system – covered in our blog earlier this year. The latest improvements allow scientists to make genetic modifications much more easily and accurately than ever before, but with these incredible advances come big questions regarding the ethics of using such a powerful tool.

Medical applications

Understandably, the potential clinical applications of gene editing attract a great deal of interest and media coverage. The most immediate priority for medical professionals is to improve gene therapy for patients with rare genetic diseases and cancers, such as baby Layla Richards, who was successfully treated for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia with cells prepared using gene editing. Researchers also hope to create better disease models for research by introducing disease-associated mutations into laboratory-grown cells.

Due to its more contentious nature, however, it is the scope for heritable (germline) genetic modification that is attracting the most attention; and which the Human Gene Editing Summit had as its primary focus. Many countries have a legal ban on the modification of human embryos – including the UK, where there are only two exceptions: genetic changes to surplus human embryos donated by couples who have had IVF treatment, for approved medical research (provided that the embryos are not grown for any longer than two weeks); or as part of approved mitochondrial donation procedures for the avoidance of severe mitochondrial disease. Both are subject to strict regulation by the Human Fertilisation & Embryology Authority (HFEA).

The thorny issue of heritable changes

Some say that the time has now come to re-evaluate the general international consensus against heritable genetic modification of human embryos, pointing out that CRISPR could become a tool for the eradication of serious inherited diseases. Others contend that the potential risks to future generations are too great, preferring pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) as the best method to help prospective parents at risk of having children affected by such diseases.

Public opinion is a major concern. Will the general population be comfortable with the prospect of making permanent genetic changes to the human genome? A negative public reaction to germ-line modification leads also to questions around, and may also slow progress towards, gene therapy for children and adults suffering from a variety of diseases. Long-standing fears of the ‘slippery slope’ effect were also raised at the conference, with concern expressed that, over time, gene editing will be used to avoid milder forms of disease, and even to control normal variation in characteristics such as intelligence or fitness – the classic ‘designer baby’ scenario; though the complex genetics behind many such attributes means that this is not feasible in the near future.

A statement from the summit’s organisers strongly supported human gene editing for medical research, but concluded that creating live babies (even for clinical purposes) would be irresponsible. However, they did not support an international ban, recommending instead regular review of the situation in terms of science, safety and societal views on the ethics of human genetic modification. There is no quick answer for these big questions, and as science and technology evolve so too will our conversation surrounding the ethics of gene modification.