Day in the life: clinical bioinformatician

In the latest article in our series, Eileen Gallagher introduces the increasingly important role that bioinformatics plays in today’s healthcare system

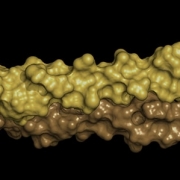

Bioinformatics is the study and analysis of biological information and is at the cutting edge of science within healthcare. With the increasing amount of genomic information that is produced, it is important that we can be sure that data is of a high quality and is processed for analysis in an appropriate and accurate way – and that’s where the bioinformatician comes in.

Bioinformatics in healthcare

Clinical bioinformaticians use their knowledge of both biology and computer science to develop and improve methods for diagnosis, and for acquiring, storing, and analysing biological data, with the aim of supporting patient care. Although they can deal with any kind of biological information, they are particularly in demand owing to the increasing use of genome sequencing, and the huge datasets that result, and therefore they are considered a vital part of the growing genomics workforce.

Bioinformatics is used both in public health and the NHS. In public health, bioinformatics is employed to investigate the health of populations, including outbreaks of infectious disease. The NHS, meanwhile, is more focused on individual health and the way in which genomics can be used to provide a diagnosis or to inform treatment of an individual.

The genomic data that clinical bioinformaticians may be asked to work on includes gene sequences, or combinations of gene sequences, and increasingly exome and whole genome sequences from both patients and pathogens.

Starting out

I trained to become a clinical bioinformatician through the NHS Scientist Training Programme run by the National School of Healthcare Science, where I focused on understanding human genetic sequences. Since completing the training, I have joined Public Health England (PHE), working in the National Infection Service. The aim of PHE is to protect and improve the nation’s health, and reduce health inequalities, so this often involves working closely with the NHS.

When people think about genome sequencing, they inevitably think about the human genome, but understanding the genomes of pathogens can also benefit health outcomes.

I work in the virus reference department (VRD), which performs a wide variety of laboratory investigations for human viral infections. Viruses ranging from common flu to those that are extremely rare in the UK, like Ebola, are studied here. The scientists use a range of methods to determine information about the virus, including genomic sequencing.

Virus genomes are smaller than human genomes, producing data ranging from around 2Kb through to 2,800Kb, but are more varied in that they can be made of either DNA or RNA, single stranded or double stranded. Variation can be incorporated much more easily into viral genomes than ours, and therefore some viruses can mutate very quickly.

A varied and challenging role

The role of a bioinformatician is diverse. It can involve writing code to create analysis pipelines, creating databases, validation of processes, or carrying out and communicating the findings of an analysis. The bioinformaticians at PHE have a wide range of responsibilities, which can be based on their knowledge or the needs of the service. The tasks they carry out on a day-to-day basis depends on the specifics of their role.

Creating pipelines to analyse genetic sequences involves stringing together several different computer programs. Some programs are already available, while others need to be created especially for a particular analysis.

These pipelines allow us to check the quality of the sequences, and investigate specific features such as drug resistance. The pipelines’ outputs should highlight information about the virus that may help with diagnosis or the identification of treatment options.

Bioinformaticians are frequently involved in creating and curating large data sets, often in databases. The information about the viruses and their sequences must be stored securely, accurately, efficiently and in a standardised way, complying with information governance standards – and this is the responsibility of bioinformaticians. Such data will hopefully allow us to understand more about viruses in the future – their resistance to drugs, for example, or how they spread – and therefore it is extremely important that it is maintained correctly.

I also assist in investigations, plotting the genomes of different strains of a virus on a diagram called a phylogenetic tree. This is a visual representation of the shared ancestry of multiple (sometimes hundreds of) genetic sequences; it resembles a branching tree, and the shorter the distance between two points along the branches, the more similar the genetic sequences represented by those points are. This information can indicate the last common ancestor of two viruses and can give us information about how fast a virus is evolving. These types of findings can be invaluable to epidemiology and in public health decision-making.

Beyond the data

Communication is an essential skill for bioinformaticians, who may be required to explain or discuss any analysis, database or pipeline with other scientists or clinicians. It is paramount that results being generated are correct and understood by all involved in patient care.

This is an aspect that I particularly enjoy, especially as I have recently had the opportunity to go into schools to discuss the role of bioinformaticians and our role within healthcare. I have also contributed to a recent short film, produced by the GEP, talking about the profession and the skills involved.

Eileen Gallagher is a clinical bioinformatician at Public Health England.

‘Day in the life’ is a series of articles commissioned by the GEP with a focus on the healthcare careers being shaped by rapid advances in genomics. Other articles in the series have been written by a trainee genetic counsellor and a genetic diabetes nurse.

–