Liquid biopsy: A closer look

We take a deep dive into the genomic test that researchers hope will improve treatment for cancer patients

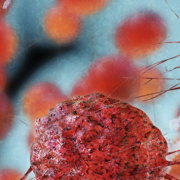

Liquid biopsies are a group of tests that look for evidence of circulating tumour DNA shed by cancer into a patient’s blood. They are a significant area of focus in current research, and with good reason: among the many advantages of liquid biopsy is the potential to revolutionise cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Uncertainties around the technology remain, however, and the NHS is currently running several pioneering trials to thoroughly measure the patient benefits. This means that you’ll likely be hearing a lot more about liquid biopsies over the coming weeks, months and years, so let’s dive in and examine exactly what they are and what they can do.

What does a liquid biopsy look for?

Circulating cell-free tumour DNA

Many (though not all) of these tests have a genomic component. Those currently being trialled by the NHS look at circulating cell-free tumour DNA (cfDNA): fragments of DNA from tumour cells that have died and been broken down. Analysis of these fragments can provide information about changes in the cancer cells’ genomes (somatic mutations), as well as about epigenetic changes caused by methylation, which affects which genes are switched on or off.

The TRACC study of bowel cancer patients currently taking place within the NHS uses a combination of both types of markers. The Galleri cancer screening test, which is also being evaluated as part of a current NHS trial, looks at methylation signatures.

Circulating tumour cells

Another type of liquid biopsy looks for the presence of metastatic cancer cells directly in the blood. The accuracy of these tests has improved significantly in recent years, and their use may increase in the future.

Circulating tumour cell screening tests are now being offered privately in the UK; however, there is a lack of evidence that they result in earlier diagnosis and treatment, with some clinical experts arguing that, at this early stage in the technology’s development, they have the potential to do more harm than good.

Who is being tested (and why)?

People with cancer (to inform treatment)

cfDNA testing can be used to gauge the effectiveness of therapies and help predict whether a patient will need further treatment. As we reported last week, the TRACC study is currently evaluating this test in patients who have had surgery to remove bowel cancers.

It can also be used as an alternative to a traditional biopsy, in order to find out more about the genetic profile of the cancer. Understanding what mutations are present in a tumour’s genome can inform personalised medicine approaches and help clinicians choose targeted treatments with the best chance of success.

Because it is possible to perform liquid biopsies at regular intervals, this test also has the potential to track changes in the cancer genome over time, allowing treatment strategies to respond.

People with symptoms (to aid diagnosis)

The NHS-Galleri trial will offer a cfDNA test to 25,000 people with suspected cancer, to see if it can help with the speed or accuracy of reaching a diagnosis. Results are expected later this year. Read more about the NHS-Galleri trial.

Healthy people (to detect cancer)

One of the most promising applications of liquid biopsy is its potential use in screening programmes to detect cancer. Many types of cancer are difficult to screen for using conventional approaches, or have few symptoms in their early stages.

Cancers diagnosed at earlier stages have better treatment outcomes, and the NHS Long Term Plan aims to increase the proportion of cancers diagnosed at stage one or two from its current level of around 50% to 75% by 2028. Current research is sharply focused on this application of the technology: as part of the NHS-Galleri trial, for instance, patients within the main cohort (140,000 individuals with no cancer symptoms going into the trial) whose results indicate possible cancer will be referred to NHS cancer services for further investigation.

While none of the liquid biopsy tests currently under trial are without flaws – the Galleri test, for instance, generated 57 false positives (cases in which the test indicated possible cancer, but on further investigation none was discovered) during a previous trial – their potential to improve cancer care is such that they are set to remain a research focus for the foreseeable future.

–