SCID gene therapy trial publishes results

This week, we look at a significant breakthrough for the treatment of severe combined immunodeficiency

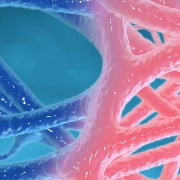

A new ‘robust’ gene therapy for severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), a condition which leaves children without an immune system, has been developed by researchers at Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) and the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

The results of a recent clinical trial, published in The New England Journal of Medicine, showed extremely promising results, with all 50 of the participants surviving after a 24- or 36-month follow-up period.

What is SCID?

SCID, is a rare disease in which children are unable to generate immune responses, leaving them vulnerable to infections that would normally be considered harmless. Without treatment, children with SCID usually die in the first year of life.

The condition is caused when a child lacks a functional copy of genes that are essential to creating a working immune system. There are a number of such genes, and variants in any of them can lead to very similar symptoms. It is important to understand the precise genetic cause in each case, however, because treatment options vary, and it can have implications for future pregnancies.

Babies with SCID usually appear healthy at birth and for a short time afterwards, while they still benefit from their mother’s antibodies. Within six months, there is a high chance of infection because they are unable to make functional lymphocytes (a type of white blood cells essential to immune system function). These infections will also be less likely to respond to standard treatments and will take longer to resolve.

Once diagnosed, children with SCID need to be kept away from all potential sources of infection. In the 1970’s, the condition was dubbed ‘bubble boy syndrome’ – named for the experience of SCID patient David Vetter who lived inside a sterile chamber for much of his life.

Existing treatments

The most common treatment for SCID is a haematopoietic stem cell transplant (bone marrow transplant) from a matched donor, which allows the child to develop a normal immune system. A good donor match is not always available, though, and there are significant risks, including graft-versus-host disease, which can be very serious.

The clinical trial at Great Ormond Street Hospital is only for one specific type of SCID called ADA-SCID.

ACA-SCID is caused by mutations in the ADA gene, which codes for the enzyme adenosine deaminase. It is rare, affecting roughly 1-in-200,000 people.

Aside from a donor stem cell transplant, the other existing treatment for ACA-SCID involves regular injections of the ADA enzyme in addition to immunoglobin-replacement therapy to provide antibodies, although care still has to be taken to minimise exposure to germs.

How the trial worked

The trial used the patients’ own cells instead of using cells from donors. The cells were extracted, and a harmless virus was used to deliver a functional copy of the ADA gene into the cells before they were put back into the participants.

Two groups of participants were selected for the study, 30 from the United States and 20 from the UK. Each group was monitored for a different length of time – 24 months and 36 months respectively.

Positive results were recorded after only three months, including increased ADA enzyme expression, and other markers of an active immune system in the patients.

After the follow-up period ended for each group, the trial demonstrated a 100% survival rate, with 48 out of 50 participants no longer having symptoms of SCID or requiring any treatment for the condition.

Sarah, one of the participants who took part in the trial, is now four years old. Her mum, Maria, said: “Six months after [Sarah] was given the gene therapy, her skin was clean and healthy, and the other symptoms got a lot better. She’s doing so well now and can do everything a normal child her age would do.”

Read more about another ground-breaking gene therapy, Zolgensma, that is changing the lives of young children affected by spinal muscular atrophy.

–