Family matters: Top tips for drawing a genetic pedigree

Genetic counsellor Megan Rogers shares her dos, don’ts and top tips for taking and drawing a patient’s family history

A family history, or genetic pedigree, is typically a diagram of three consecutive generations, both maternal and paternal family, and includes names, dates of birth and death, and relatives’ medical history. However, this integral component of clinical genetics practice is more than a medical who’s who of a patient’s family, writes genetic counsellor Megan Rogers.

A detailed family history can help health professionals identify inheritance patterns, recognise those affected or at risk of an inherited condition, and provide valuable clues for an hereditary diagnosis.

Exploring the patient’s family history also helps to build rapport with the patient and provides them with a real-life concept of genetics. Sharing information that they are ‘expert’ in – their own family – gives them a chance to discuss something that they know, and you don’t.

Building the picture of the patient’s family also provides a glimpse into the dynamics at play and creates opportunities for discussing the impact of genetics on the wider family.

The family history can also be instrumental in interpreting genetic test results, particularly variants of uncertain significance (VUS). Assessing these gene variants in the context of a family history can help determine whether the VUS is the cause of the patient’s health concerns or a unique part of their genetic make-up with little or no clinical implication.

Family history dos and don’ts

Do start by explaining the purpose of a family history, the types of information you will ask about, and that it is not a test. Not knowing all of their relatives’ details is okay.

Be sure to ask for your patient’s permission before collecting family history information and thank them for sharing this with you. You will need to ask about sensitive topics including consanguinity and pregnancy history. Explain that we ask everyone these questions when drawing a family history, and that identifying consanguinity can help us know if there is a risk of a condition being inherited from both sides of the family.

It can be helpful to clarify whether children and siblings have the same mother and father. Also include adopted family members. Although they are not at risk of inheriting the condition in the family, they are part of your patient’s family and the condition might impact them in other ways.

What NOT to do:

Don’t make assumptions. Clarify details, such as relationships, sex/gender, adoption status, if unclear.

Don’t use the word ‘pedigree’; it often reminds patients of dogs.

Don’t push patients to share details that they’re not comfortable discussing; for example, full names or dates of birth of relatives for privacy reasons. If necessary, these can be addressed later.

Don’t write anything on the family history that you don’t want the patient to see. While it is typical to draw a line through a deceased relative’s symbol, if you feel that would be insensitive, you can instead put a small cross next to their name and make sure to write “d. age –“.

Case example: A future changed by history

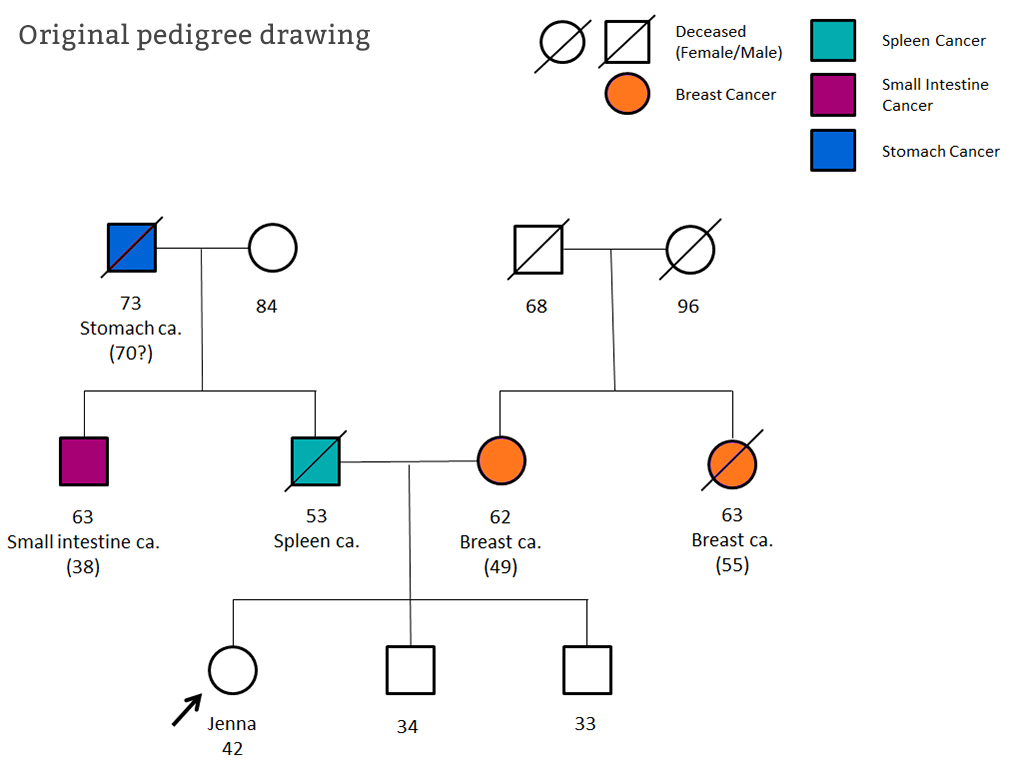

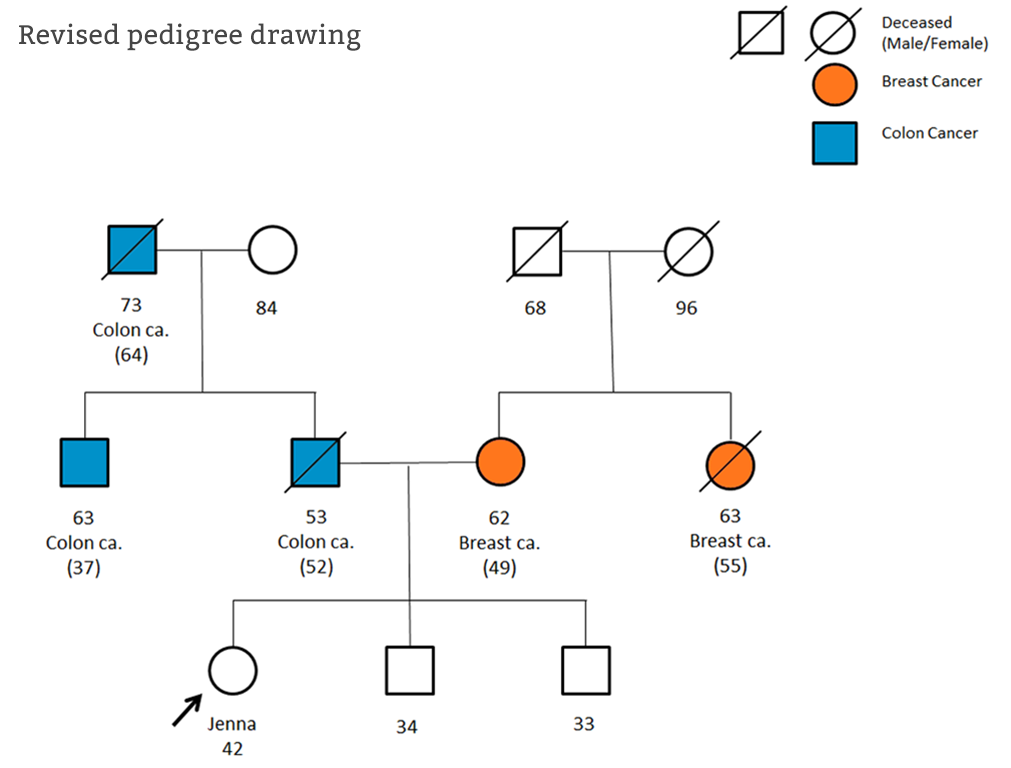

Jenna* was referred to Clinical Genetics aged 42. She was worried about her breast cancer risk and had reported that her mother and aunt had both been diagnosed with breast cancer around age 50. The referral also suggested a vague cancer history on her father’s side. During her appointment, both sides of Jenna’s family history were thoroughly explored and the cancers that Jenna reported were recorded along with names and dates of birth.

Following the appointment, medical records were requested to confirm the cancer diagnoses reported. It became apparent that the cancers in Jenna’s paternal family were in fact bowel cancers and together were suspicious of a hereditary cancer syndrome called Lynch syndrome.

Genetic testing was offered to Jenna’s uncle and a gene alteration confirming Lynch syndrome was found. Through thorough exploration of Jenna’s family history, the unexpected Lynch syndrome diagnosis was made, which allowed Jenna and her family to access genetic testing and appropriate screening to reduce their cancer risk.

*Patient details have been changed to maintain patient confidentiality.

Top tips for beginners

- Take your time. Most patients are grateful for the opportunity to discuss their family history and have you spend time exploring it with them.

- Don’t worry too much about being ‘perfect’. You can re-draw the family history after clinic if necessary.

- Don’t be afraid to ask questions. Some topics in a family history might be sensitive but people are quite understanding when you explain why the information is helpful.

- Be flexible. The start of the appointment often feels like the best time to collect the family history, but sometimes patients will have other concerns or questions that will take priority. You can always return to complete the family history later in the appointment.

- Remember why you’re collecting family history. Ask targeted questions to find out if other family members have the same or related conditions.

- Details are not always necessary for every relative, for example exact date of birth. Some people find it stressful remembering these, so instead see if they know approximate ages.

- Practice makes (almost) perfect. The process might feel long and tedious to begin with, but it does come naturally over time. And it’s worth the effort: a good family history can make all the difference for a patient.

Help patients help you

If a patient asks how they can prepare for a family history consultation, you could suggest:

- If possible, speak with your relatives and ask about medical conditions in the family.

- If known, make a note of the ages and types of diagnoses in the family, and if possible the names and dates of births for ‘affected’ relatives.

- If you have copies of medical records or death certificates, these can be useful as well.

Understandably, it can sometimes be difficult for patients to speak to family members about health problems. It can also feel awkward sharing private family details with a health professional. Reassure your patient that what they might think is peculiar is usually completely ordinary. Ultimately, any information they can provide will likely help you to help them.

Megan Rogers is a genetic counsellor at University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust

–