Repeat expansion disorders

Repeat expansion disorders are a group of conditions caused by the pathological expansion of intragenic nucleotide repeats.

Overview

Our genomic DNA contains many stretches of simple repetitive sequences. Collectively these are known as ‘microsatellites’, and they typically contain between one and six nucleotides, repeated multiple times. Sometimes repetitive sequences can occur within genes. In this case, expansion of the sequence can affect the level of expression and/or the function of the gene product.

Expansion of nucleotide repeat sequences within certain genes can be disease-causing and has been identified as the mechanism underlying a group of inherited conditions known collectively as the ‘repeat expansion disorders’. These are sometimes called ‘triplet repeat expansion disorders’ as trinucleotide repeats are by far the most common, but a number of other base-pair repeats sizes have been identified.

Inheritance can be autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive or X-linked.

What are the repeat expansion disorders?

For reasons that are not fully understood, the repeat expansion disorders identified thus far are almost exclusively neurological and neuromuscular. They include:

- fragile X syndrome;

- myotonic dystrophy type 1 and type 2;

- spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy;

- Friedreich ataxia;

- common spinocerebellar ataxias;

- Huntington disease; and

- c9orf72-related fronto-temporal dementia and/or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; and

- CANVAS (cerebellar ataxia, neuropathy and vestibular areflexia syndrome).

What causes repeat expansion disorders to occur?

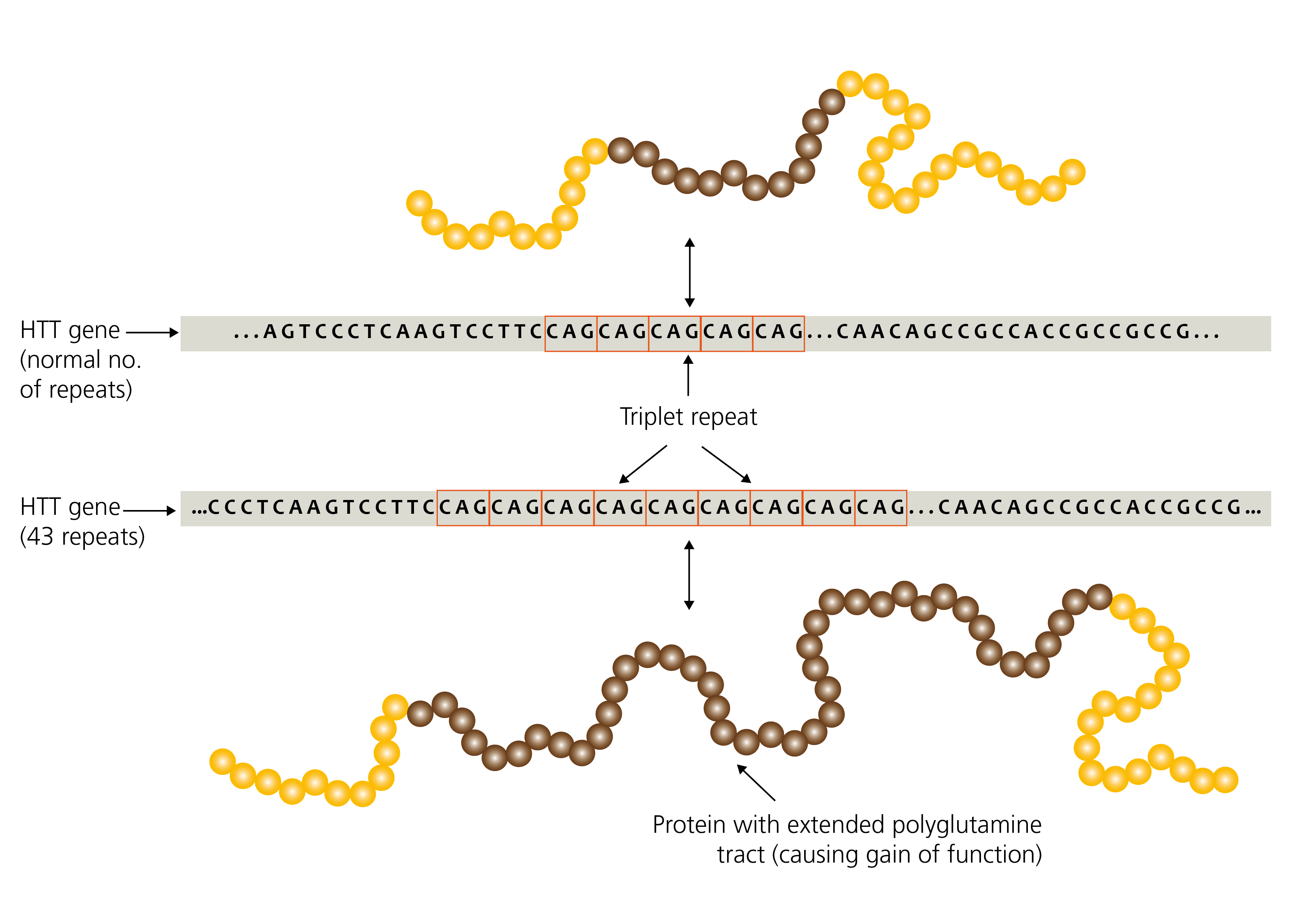

Figure 1: Expansion repeats in the HTT gene (unaffected vs Huntington disease)

Repetitive sequences are inherently unstable during DNA replication and are therefore prone to expand or contract in length during DNA replication, both somatically and in the germline.

Therefore, unlike other pathogenic variants that are usually passed unchanged from parent to child (such as single nucleotide variants, deletions, duplications and so on), repeat expansions are ‘dynamic’ due to their tendency to change further in size during DNA replication.

Repeat size and severity

Increasing repeat size is associated with increasing instability of the region. An unaffected individual will have a repeat size within a small range, which tends to remain within that range when passed to the next generation. For all known repeat expansion disorders, there is a threshold for instability when the number of repeats has increased to fall within the ‘premutation’ range. At this point, there is an increased risk of expansion into the ‘full mutation’ range on transmission from parent to child. This explains why some individuals are affected despite a lack of family history of similar symptoms.

An increasing repeat size in successive generations can lead to earlier onset of symptoms and greater disease severity. This phenomenon, known as ‘anticipation’, can be associated with childhood onset in what would otherwise typically be adult-onset conditions.

There may also be a gender effect on likelihood of transmission. For example, paternal transmission is more commonly associated with an increased repeat size and earlier onset in Huntington disease, whereas maternal transmission is associated with the prenatal onset of congenital myotonic dystrophy type 1.

For some conditions, presence of a ‘premutation’ predisposes to development of symptoms which may or may not be similar to that of individuals with a ‘full mutation’. For example, individuals with a fragile X premutation may be at risk of premature ovarian failure and/or fragile X tremor ataxia syndrome.

Smaller repeat sizes in some genes may be reported as possible disease modifiers or risk factors for other neurological disorders. For an individual patient the predictive value of such risk factors is uncertain and it may not be possible to offer predictive testing to relatives of an affected individual.

Can we identify the number of repeats?

For most repeat expansions (but not all), it is possible to accurately calculate the number of repeats in blood-derived DNA using current molecular techniques, and this number may be included in the laboratory report. Myotonic dystrophy type 1 is an example of a situation in which this is not routinely possible, as repeat sizes above 130 are challenging to size accurately.

Although repeat size is important, it does not correlate with sufficient accuracy to predict symptom onset, disease progression or severity. For example, the presence of a C9orf72 expansion does not predict whether an individual will develop frontotemporal dementia or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neurone disease, or both conditions, or if they will be entirely unaffected during their lifetime.

Repeat size can also be affected by other factors such as interruptions and somatic expansions. Confirmation and clinical relevance of such variability is not yet sufficiently understood to offer as part of routine genomic testing.

How do we test for repeat expansion disorders?

Repeat expansion disorders are not picked up by array CGH or DNA sequencing, so specialist short tandem repeat (STR) testing is required. In recent years, additional repeat expansion disorders with more complex genetic variation have been identified. Thus routine testing for this group of conditions is technically challenging. Currently, testing is done using PCR-based techniques, but research suggests that whole genome sequencing may become a viable option.

Resources

For clinicians

- NHS England Genomics Education Programme: Repeat after me: what are repeat expansion disorders? (explainer blog article)

References:

- La Spada AR, Taylor JP. ‘Repeat expansion disease: progress and puzzles in disease pathogenesis’. Nature Reviews Genetics 2010: volume 11, pages 247–258. DOI: 10.1038/nrg2748

- Chen Z, Morris HR, Polke J. ‘Repeat expansion disorders‘. Practical Neurology 2025: volume 25, issue 3, pages 204-216. DOI 10.1136/pn-2023-003938

- Nelson DL, Orr HT, Warren ST. ‘The unstable repeats: Three evolving faces of neurological disease’. Neuron 2013: volume 77, issue 5, pages 825–843. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.02.022