Mental health and rare disease

Rare genetic conditions are often chronic and medically complex, and can take years to diagnose. It has been well documented that living with a rare genetic condition can negatively impact mental health, and poor mental health has a detrimental effect on physical symptoms.

What is good mental health?

Good mental health is a state of wellbeing that enables patients and their families to cope with the stresses of life, learn and work well, and develop and maintain positive relationships. This is all crucial to a person’s quality of life. Having good mental health can also help individuals to manage the uncertainties that come with living with a rare disease.

What contributes to poor mental health among rare disease patients?

Rare conditions can have a significant impact on mental health due to their effects on daily life (see figure 1). The challenges of living with a rare condition may include:

- chronic pain and fatigue;

- mobility issues;

- changes to physical appearance;

- unpleasant tests and treatments; and

- lack of information and disease awareness.

This all contributes to an increased risk of depression, anxiety and stress in patients and their families and/or caregivers.

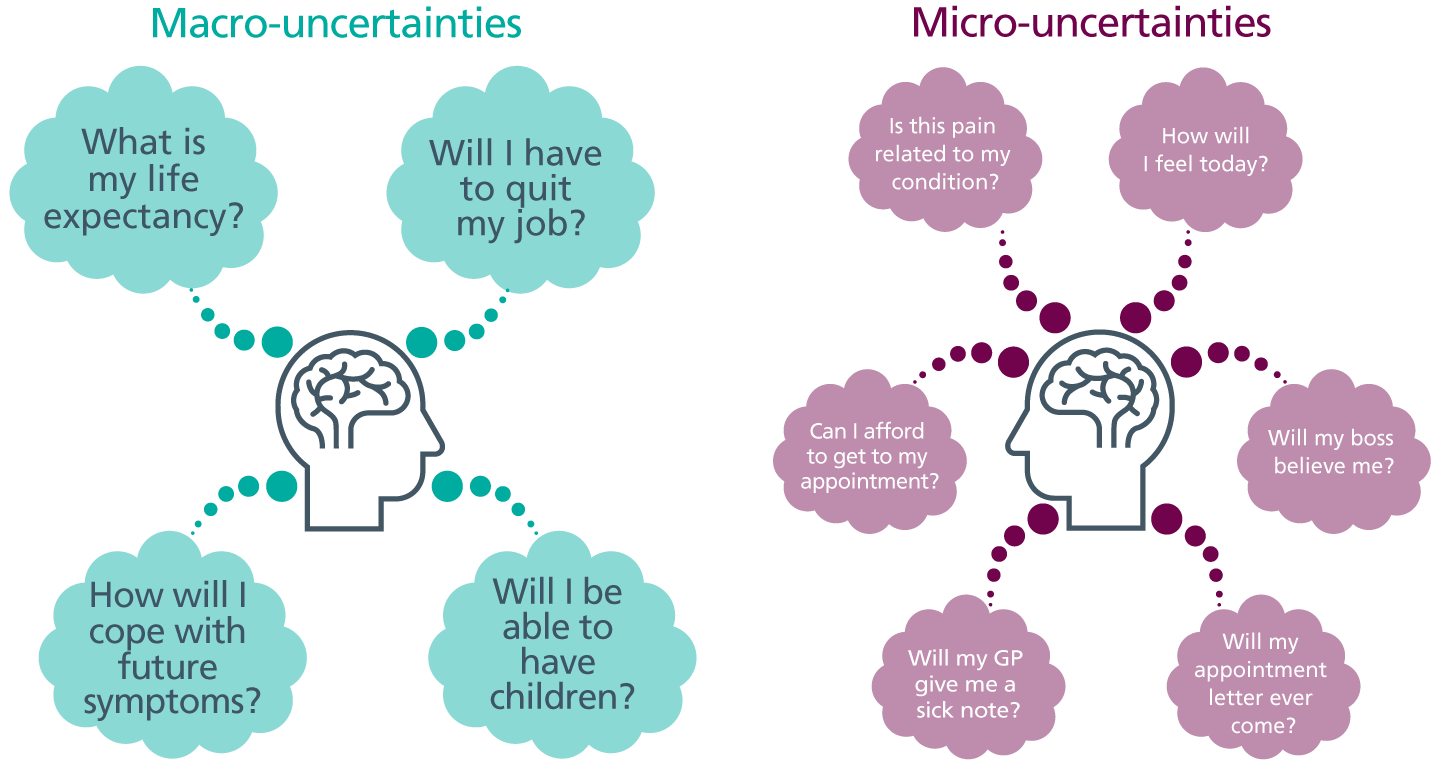

Figure 1: The uncertainties of rare disease

As figure 1 shows, rare disease patients live with a lot of uncertainty. These can be split into ‘macro-uncertainties’ (that is, the big questions about how a condition will impact a person’s life) and ‘micro-uncertainties’ (the day-to-day concerns about things like getting to appointments and being listened to by an employer).

If symptoms are misdiagnosed or not joined up, feelings of frustration and distress are common. Unresolved physical health problems can contribute to depression and anxiety, especially when paired with doubts or dismissal from healthcare professionals. Some patients report being told things like, “It’s all in your head,” which can lead to reduced trust in the healthcare system.

Research published in 2022 by Rare Disease UK reports that more than 90% of study respondents felt anxious, stressed or depressed due to their rare condition, and that 36% of patients and 19% of carers had experienced suicidal thoughts. These findings indicate that access to professional psychological support must be improved for rare disease patients and their families.

The impact of rare genetic conditions on family dynamics

The impact of rare disease can never be truly understood without looking at it from the perspective of the patient’s family members, among whom anxiety, grief and emotional strain are all common.

For example, siblings of a child with a rare condition may feel disoriented and neglected as their family dynamics shift and their own needs may be inadvertently overlooked. In addition, as more therapies for rare genetic conditions are becoming available, some younger family members may benefit from treatment that their older relatives did not have access to.

Guilt is also common among families with rare conditions. Parents may blame themselves for passing on a genetic variant while simultaneously grappling with the overwhelming responsibility of caring for a child with complex medical needs. Likewise, a relative who was at risk of inheriting a condition may feel guilty for not having it when another family member does. Family members may also experience compassion fatigue when caring for their ill relative(s).

Communicating with rare disease patients

As a healthcare professional, supporting the mental health and wellbeing needs of a rare disease patient involves prevention as well as crisis interventions – and it all starts with good communication. The way in which information is delivered to a patient can stay with them for the rest of their life.

Delivering a diagnosis

The emotional impact of any diagnosis will depend on whether it has been sought out or is unexpected (that is, the result of an incidental finding from other investigations). When delivering news of a diagnosis, it is important for healthcare professionals to be mindful of the patient’s experience.

To help when breaking difficult news, prepare your patient by letting them know they will receive a diagnosis, and give plenty of time for their appointment. Avoid delivering a diagnosis via phone or letter, and arrange a follow-up appointment soon after to answer any questions that have arisen. It is crucial not to overwhelm the patient and to signpost them to more information and support.

The early days after a diagnosis may involve urgent treatment and tests, which can be invasive, as well as following up on family members if the condition can be inherited. Many people may not be able to take in every detail during the initial diagnosis delivery, which is why good communication from the beginning is fundamental in managing patient and family distress.

Language and terminology

Some words and terms have different connotations in different situations. For example, using the word ‘mutation’ to describe a genetic variant is common within scientific communities, especially within cancer genetics; however, using it to describe a gene change that means someone’s baby will have a rare disease is very different.

In addition, it is important to avoid using terminology that inadvertently defines someone by their condition or implies that they were active in a passive situation – for example, rather than saying, “She passed the condition on to her son”, you should say, “The condition was inherited”.

For more information about language and terminology, take a look at this language guide published by Genomics England.

Integrating mental health into patient care

The mental health of rare disease patients requires assessment, and monitoring should be an integral part of care plans, considered equally as important as physical health. Remember that poor coordination of care can have a significantly negative impact on a patient’s quality of life. There are three key things you can do to integrate mental health into rare disease patient care.

- Refer your patient to a patient advocacy group. These groups have access to resources and strategies to improve emotional wellbeing. Genetic Alliance UK provides a list of groups, and you can contact Medics for Rare Disease or Rare Disease UK directly for advice. Rareminds can also help with signposting for counselling.

- Ask the patient directly: “How are you coping?” Asking a patient what they are finding most difficult about their condition helps to promote patient-centred care, and can make all the difference when someone is on the brink of a mental health crisis.

- Address micro-uncertainties. Protect your patient from further anxiety by making micro-uncertainties more predictable wherever possible. For example, be clear about follow-ups (when to expect an appointment, what to do if it does not arrive), and coordinate their care wherever you can by contacting other healthcare professionals involved and taking accurate notes. You can also ‘safety net’ their care by ensuring they know who to contact (and how) for out-of-hours concerns. Finally, stick to commitments by calling when you say you will or letting them know if you need to reschedule.

Resources

For clinicians

- Genetic Alliance UK: A-Z directory of member organisations

- Genomics England: Language and terminology (PDF, nine pages)

- International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies: What is medical trauma? (PDF, two pages)

- Medics for Rare Disease: Available courses

- NHS England Genomics Education Programme: Let’s talk about uncertainty

- Rareminds

- What Matters to You? (a campaign by Healthcare Improvement Scotland)

References:

- Spencer-Tansley R, Meade N, Ali F and others. ‘Mental health care for rare disease in the UK: Recommendations from a quantitative survey and multi-stakeholder workshop’. British Medical Council Health Services Research 2022: volume 22, issue 1, page 648. DOI: 1186/s12913-022-08060-9