Single nucleotide variants

A single nucleotide variant is a DNA change at a single base or nucleotide position in the genome sequence.

How do single nucleotide variants arise?

Our genome is made up of four different nucleotides: adenine, cytosine, thymine and guanine (A, C, T, G), which occur in a specific sequence. A sequence of three nucleotides codes for an amino acid. Single nucleotide variants (SNVs) can arise by chance, through impaired DNA repair, or via increased variation in the genome due to mutagens such as radiation and genotoxic chemicals. Insertion or deletion of nucleotides can also occur, and can result in frameshift variants.

Types of SNVs

There are several types of SNV that can occur in the genome. Whether the change results in disease depends on its size, its position and its effect on protein production. SNVs can be grouped into:

- synonymous;

- non-synonymous; and

- stop-gain.

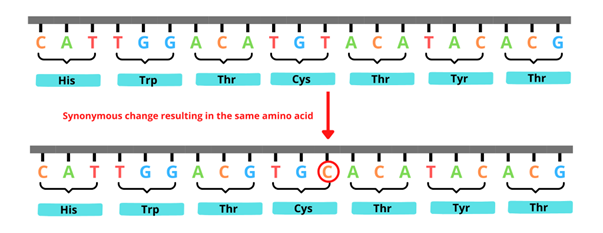

Synonymous SNVs

In the case of synonymous SNVs, although the original nucleotide is substituted with a different nucleotide, the same amino acid is produced (this is because each amino acid can be encoded by different combinations of nucleotides) – see figure 1.

Although synonymous changes often don’t cause disease, if they occur at sites that regulate protein production, they can be pathogenic (disease-causing).

Figure 1: An example of a synonymous variant

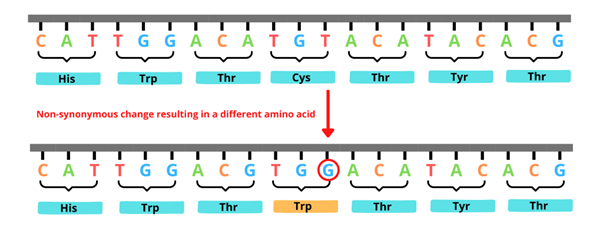

Non-synonymous SNVs

Non-synonymous SNVs are also known as missense variants. Here, the nucleotide that is substituted results in the coding of a different amino acid (see figure 2). Depending on how vital that amino acid is to the final protein structure and function, these non-synonymous variants may or may not be pathogenic.

Figure 2: An example of a non-synonymous variant

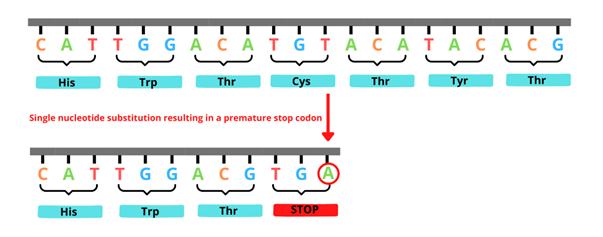

Stop-gain SNVs

Stop-gain SNVs are also known as nonsense variants. With these variants, the nucleotide substitution results in the coding of an amino acid which tells the cell to stop building the protein (see figure 3). This premature termination of the protein generally renders it non-functional.

Figure 3: An example of a stop-gain variant

So what are single nucleotide polymorphisms, then?

If these SNVs occur in at least 1% of the population, they are referred to as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs, pronounced ‘snips’). These are the most common cause of genetic variation, found about every 300 bases within the human genome. They play a significant role in normal genomic variation, but can also influence predisposition to certain diseases and our response to medication.

Key messages

- SNVs occur when there is a substitution at one position in the DNA sequence, with stop-gain variants being the most likely to cause disease and synonymous SNVs being the least likely.

- Depending on the type of change, these variants can:

-

- be the direct cause of rare conditions;

- alter the risk of developing common health problems; or

- have no discernible phenotypic effect at all.

- The terms SNV and SNP are not interchangeable: SNPs are more common, occurring in at least 1% of the population.

Resources

For clinicians

- GeneCards: the Human Gene Database

- National Center for Biotechnology Information: dbSNP (single nucleotide polymorphism database)