PARP inhibitors

PARP inhibitors are routinely used in the treatment of ovarian cancer and selected breast and prostate cancers. Clinical trials are ongoing to determine efficacy in other tumour types. The choice of which PARP inhibitor to use may be affected by constitutional (germline) and/or somatic (tumour) BRCA1 and BRCA2 variant status.

What are PARP inhibitors and how do they work?

Poly-ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors are a class of targeted cancer drug that works by taking advantage of the impaired DNA repair mechanisms in some cancer cells, leading to selective cancer cell death.

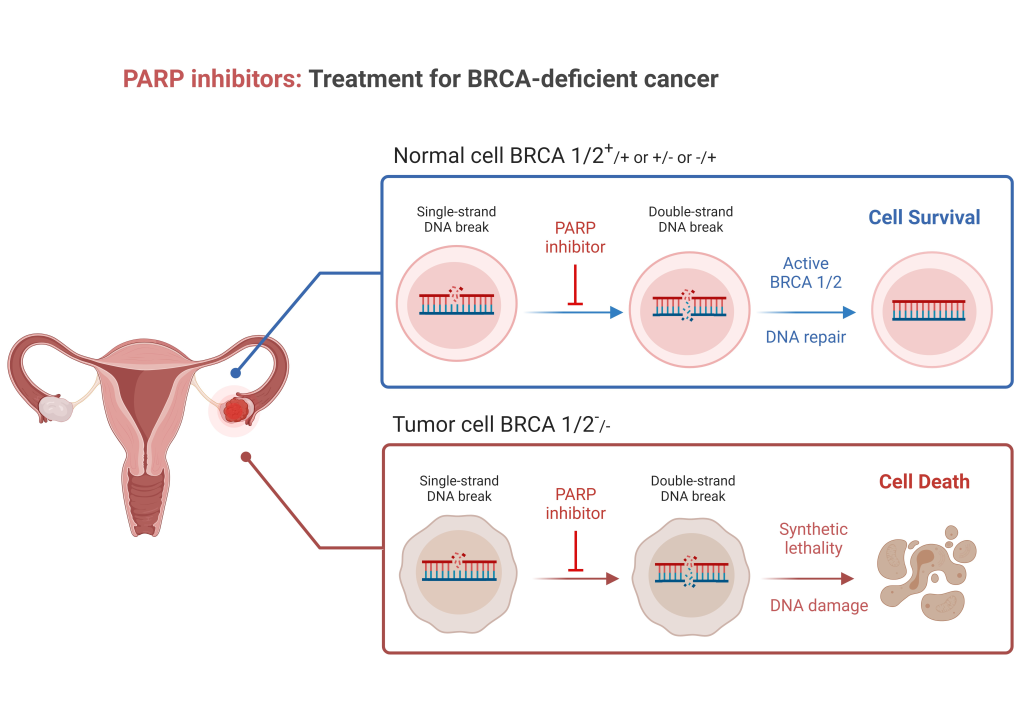

PARP is an enzyme that is involved in repairing single-strand DNA breaks. PARP inhibitors trap PARP at sites of DNA damage, leading to an accumulation of unrepaired single-strand breaks that result in the collapse of replication forks during DNA replication, thus leading to double-strand breaks.

In cancer cells that are deficient in homologous recombination (HR), these double-strand breaks cannot be repaired, resulting in high levels of genomic instability and cell death. Cells with constitutional (germline) and/or somatic (tumour) variants in BRCA1 and/or BRCA2, or in other genes associated with HR repair, may be HR deficient (HRD).

The selective toxicity that PARP inhibitors exhibit in HR-deficient cancer cells is termed synthetic lethality. The term describes the phenomenon in which a defect in one gene or pathway is compatible with cell viability, but when combined with a defect in another gene or pathway leads to cell death.

PARP inhibitors currently available include olaparib, rucaparib and niraparib, all of which are oral medications. Reported toxicities include:

- increased risk of infection, anaemia and bleeding as a result of myelosuppression;

- tiredness;

- nausea and/or vomiting;

- mouth soreness and taste changes;

- diarrhoea;

- headache;

- fatigue;

- dizziness; and

- alteration in liver and renal function.

PARP inhibitors in ovarian cancer

PARP inhibitors are particularly effective against BRCA-deficient cancer cells, and were initially reserved for ovarian cancers associated with constitutional (germline) or somatic (tumour) BRCA1 or BRCA2 variants. Their use has now been expanded to include patients without such variants, following evidence from clinical trials that they can be beneficial to all patients.

- NICE guidelines recommend olaparib for the maintenance treatment of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation-positive, advanced, high-grade epithelial ovarian cancer that has responded to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy (see SOLO1 trial).

- Patients without evidence of a BRCA1 or BRCA2 variant are eligible for first-line maintenance treatment with other PARP inhibitors (see PRIMA and PAOLA-1 trials).

- NICE 2021 guidelines recommend olaparib in combination with bevacizumab for use within the Cancer Drugs Fund for patients with HR-deficient tumours as an option for maintenance treatment when there has been a complete or partial response after first-line platinum-based chemotherapy plus bevacizumab.

- Patients who have not received PARP inhibitors in the first-line maintenance setting can receive them in the relapsed disease maintenance setting if their cancer has demonstrated response to platinum-based chemotherapy, regardless of BRCA1 or BRCA2 status or HR deficiency (see NOVA and ARIEL3 trials).

Created in and exported from biorender.com.

Figure 1: Tumours that are BRCA-deficient are not able to repair double-stranded DNA breaks ordinarily repaired by homologous recombination. PARP is used for repair of single-stranded DNA breaks. When PARP inhibitors are used, cells that are BRCA-deficient cannot effectively repair single- or double-stranded DNA damage, such that the damage overwhelms the cell, leading to cell death. Tumours that are not BRCA-deficient can repair double-stranded DNA damage, such that the cells are not reliant on PARP and are therefore not prone to PARP-inhibitor induced cell death.

PARP inhibitors in breast cancer

PARP inhibitors have been licensed in Europe for the second-line treatment of metastatic human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative breast cancer in patients with a constitutional (germline) BRCA1 or BRCA2 variant on the basis of the OlympiAD and EMBRACA clinical trials. These trials demonstrated improvements in progression-free survival with olaparib and talazoparib respectively compared to standard chemotherapy treatments. NICE has recently issued guidance recommending talazoparib for the treatment of HER2-negative, locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer in those with constitutional (germline) BRCA1 or BRCA2 variants if they have had an anthracycline or a taxane, or both (along with endocrine therapy if they have hormone receptor (HR)-positive breast cancer).

The OlympiAD study reported a significant improvement in both invasive disease-free survival and overall survival associated with the use of the PARP inhibitor olaparib as an adjuvant therapy after standard neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy for HER2-negative early breast cancer in patients with a constitutional (germline) BRCA1 or BRCA2 variant. This treatment option was approved by NICE in April 2023 and is now available via the Cancer Drugs Fund. Other breast cancer clinical trials such as PARTNER are currently investigating the use of PARP inhibitors in the neoadjuvant treatment setting.

PARP inhibitors in other cancers

The PARP inhibitor olaparib has been approved by NICE for use in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer associated with constitutional (germline) or somatic (tumour) BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants. This recommendation is based on the results of the TOPARP-B and PROfound clinical trials.

Olaparib has been licensed by the European Medicines Authority for maintenance treatment of adult patients with constitutional (germline) BRCA1 or BRCA2 variants who have metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas and have not progressed after over 16 weeks of platinum treatment within a first-line chemotherapy regimen (based on the phase three POLO trial results). However, it has not been approved by NICE.

Use of PARP inhibitors in other tumour types is currently limited to clinical trials.

Resources

For clinicians

- NICE: Olaparib for adjuvant treatment of BRCA mutation-positive HER2-negative high-risk early breast cancer after chemotherapy

- NICE: Olaparib for maintenance treatment of BRCA mutation-positive advanced ovarian, fallopian tube or peritoneal cancer after response to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy

- NICE: Olaparib for previously treated BRCA mutation-positive hormone-relapsed metastatic prostate cancer

- NICE: Olaparib plus bevacizumab for maintenance treatment of advanced ovarian, fallopian tube or primary peritoneal cancer

- NICE: Talazoparib for treating HER2-negative advanced breast cancer with germline BRCA mutations

References:

- Ashworth A. ‘A synthetic lethal therapeutic approach: Poly(ADP) ribose polymerase inhibitors for the treatment of cancers deficient in DNA double-strand break repair‘. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2008: volume 26, issue 22, pages 3,785–3,790. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.0812

- Coleman RL, Oza AM, Lorusso D and others. ‘Rucaparib maintenance treatment for recurrent ovarian carcinoma after response to platinum therapy (ARIEL3): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial‘. The Lancet 2017: volume 390, issue 10,106, pages 1,949–1,961. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32440-6

- Franzese E, Centonze S, Diana A and others. ‘PARP inhibitors in ovarian cancer‘. Cancer Treatment Reviews 2019: volume 73, pages 1–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.12.002

- Golan T, Hammel P, Reni M, and others. ‘Maintenance olaparib for germline BRCA-mutated metastatic pancreatic cancer‘. The New England Journal of Medicine 2019: volume 381, issue 4, pages 317–327. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903387

- González-Martín A, Pothuri B, Vergote I and others. ‘Niraparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer‘. The New England Journal of Medicine 2019: volume 381, issue 25, pages 2,391–2,402. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910962

- Kindler HL, Hammel P, Reni M and others. ‘Overall survival rates from the POLO trial: A phase III study of active maintenance olaparib versus placebo for germline BRCA-mutated metastatic pancreatic cancer‘. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2022: volume 40, issue 34, pages 3,929–3,939. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.21.01604

- Konstantinopoulos PA, Ceccaldi R, Shapiro GI and others. ‘Homologous recombination deficiency: Exploiting the fundamental vulnerability of ovarian cancer‘. Cancer Discovery 2015: volume 5, issue 11, pages 1,137–1,154. DOI: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0714

- Litton JK, Rugo HS, Ettl J and others. ‘Talazoparib in patients with advanced breast cancer and a germline BRCA mutation‘. The New England Journal of Medicine 2018: volume 379, issue 8, pages 753–763. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1802905

- Mateo J, Porta N, Bianchini D and others. ‘Olaparib in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with DNA repair gene aberrations (TOPARP-B): A multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial‘. The Lancet Oncology 2020: volume 21, issue 1, pages 162–174. DOI: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30684-9

- Mirza MR, Monk BJ, Herrstedt J and others. ‘Niraparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer‘. The New England Journal of Medicine 2016: volume 375, issue 22, pages 2,154–2,164. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611310

- Moore K, Colombo N, Scambia G and others. ‘Maintenance olaparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer‘. The New England Journal of Medicine 2018: volume 379, issue 26, pages 2,495–2,505. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1810858

- Ray-Coquard I, Pautier P, Pignata S and others. ‘Olaparib plus bevacizumab as first-line maintenance in ovarian cancer‘. The New England Journal of Medicine 2019: volume 381, issue 25, pages 2,416–2,428. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911361

- Robson M, Im SA, Senkus E and others. ‘Olaparib for metastatic breast cancer in patients with a germline BRCA mutation‘. The New England Journal of Medicine 2017: volume 377, issue 6, pages 523–533. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706450

- Sandhu SK, Hussain M, Mateo J and others. ‘PROfound: Phase III study of olaparib versus enzalutamide or abiraterone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) with homologous recombination repair (HRR) gene alterations‘. Annals of Oncology 2019: volume 30, supplement 9, pages IX188–IX189. DOI: 10.1093/annonc/mdz446.007

- Tutt ANJ, Garber JE, Kaufman B and others. ‘Adjuvant olaparib for patients with BRCA1- or BRCA2-mutated breast cancer‘. The New England Journal of Medicine 2021: volume 384, issue 25, pages 2,394–2,405. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2105215