Multiple monogenic benign tumours

The term ‘multiple monogenic benign tumours’ encompasses a range of genetic conditions in which individuals tend to develop three or more benign skin tumours. They can be associated with underlying cancer risk.

Overview

Affected individuals present with multiple benign skin lesions that typically become evident in adolescence or adulthood. The lesions, such as cylindromas, trichoepitheliomas and fibrofolliculomas, are the hallmark of several distinct syndromes (such as CYLD cutaneous syndrome, Lynch syndrome – or the Muir-Torre variant of Lynch syndrome – and Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome). While the tumours are benign, they serve as key clinical markers for genomic testing to identify the specific causative variant, with the underlying conditions inherited in an autosomal dominant manner in most cases.

Clinical features

- Multiple lesions: Three or more benign skin tumours, often confirmed histologically.

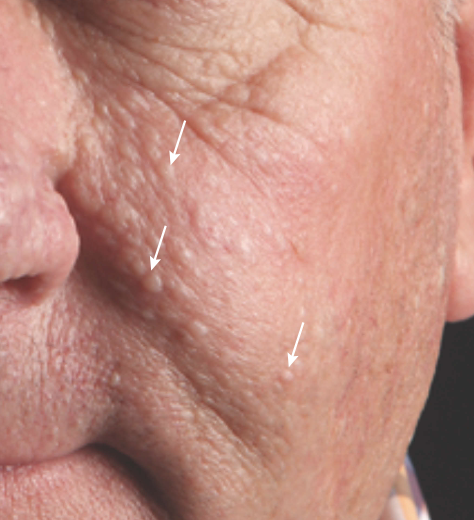

- Morphology: Lesions can be of different sizes and can be skin coloured. They are difficult to distinguish clinically and histologically, and include cylindromas, trichoepitheliomas, fibrofolliculomas and related skin adnexal tumours.

- Distribution: Lesions are commonly seen on the head, face, neck and upper trunk.

- Associated features: In some syndromes, skin findings may coexist with extracutaneous manifestations (for example, visceral cancers in Lynch syndrome or pulmonary and renal features in Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome).

Figure 1: Facial benign tumours seen in Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome

Source: Brown S, Brennan P and Rajan N 2017 (see resources section for full reference).

Genomics

Patients with multiple monogenic benign tumours usually carry monogenic pathogenic variants, with the specific gene implicated varying by syndrome. For example:

- pathogenic variants in the CYLD gene cause CYLD cutaneous syndrome (encompassing Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, multiple familial trichoepithelioma and familial cylindromatosis);

- pathogenic variants in the FLCN gene cause Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome;

- pathogenic variants in mismatch repair genes (most commonly MSH2, but also MLH1, MSH6 and PMS2) cause Lynch syndrome; and

- pathogenic variants in the LEMD3 gene cause Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome.

Variants in these genes are inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern. To inform variant interpretation from genomic testing, it is important to include as much detail regarding the patient phenotype and the family history as possible. The findings are important not only for confirming the diagnosis, but also for guiding further clinical surveillance of syndrome-specific risks.

For detailed guidance on the syndromes that can cause multiple monogenic benign tumours, and genomic testing in this scenario, see Patient with multiple benign skin tumours with a suspected genetic cause.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on:

- clinical evaluation: detailed assessment focusing on the number, distribution and morphology of skin lesions;

- histological confirmation: biopsy of at least two skin lesions to confirm benign pathology;

- family history: collection of detailed family history to identify possible autosomal dominant inheritance; and

- genomic testing.

Inheritance and genomic counselling

These conditions are rare, and incidence varies by condition. For example:

- CYLD cutaneous syndrome is estimated to affect more than 1 in 100,000 individuals; and

- the Muir-Torre phenotype is estimated to affect approximately 10% of patients with Lynch syndrome, which has an estimated population prevalence of 1:279.

Individuals affected by an autosomal dominant condition have one working copy of the gene, and one with a pathogenic variant. The chance of a child inheriting the gene with the variant from an affected parent is one in two (50%). Incomplete penetrance can occur, which means that not everyone who has the variant develops the disease.

Management

Management is dependent upon the causative gene. General management principles include:

- surveillance: counselling the patient to perform regular skin self-examination, with follow-up with dermatologists as needed, and radiological monitoring for internal cancers (dependent upon the specific syndrome);

- local treatment: options such as surgical removal or laser therapy for lesions that cause cosmetic concerns or symptoms;

- future therapies: although no targeted genetic therapies are yet standard, evolving research may allow specific interventions based on the genetic etiology; and

- referral of affected patients to clinical genetics, which should be considered to discuss onward management, family planning implications and cascade testing of relatives at risk.

Resources

For clinicians

- GeneReviews: Birt-Hogg-Dubé Syndrome

- GeneReviews: CYLD cutaneous Syndrome

- Genomics England: NHS Genomic Medicine Service (GMS) Signed Off Panels Resource

- NHS England: National Genomic Test Directory

- US National Library of Medicine: ClinicalTrials.gov database

References:

- Brown S, Brennan P and Rajan N. ‘Inherited skin tumour syndromes‘. Clinical Medicine 2017: volume 17, issue 6, pages 562–567. DOI: 10.7861/clinmedicine.17-6-562

- Horton A, Fostier W, Winship I and others. ‘Facial features of hereditary cancer disposition‘. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2024: volume 20, issue 9, pages 1,182–1,197. DOI: 10.1200/OP.23.00610

For patients

- BHD Foundation

- British Association of Dermatologists: Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome

- British Association of Dermatologists: CYLD cutaneous syndrome