Inherited epidermal differentiation disorders

Epidermal differentiation disorders, previously known as ichthyoses, are a heterogenous group of genetic conditions affecting the formation and maintenance of the top layer of the skin. They are characterised by abnormal scaling, dryness and redness of the skin.

Overview

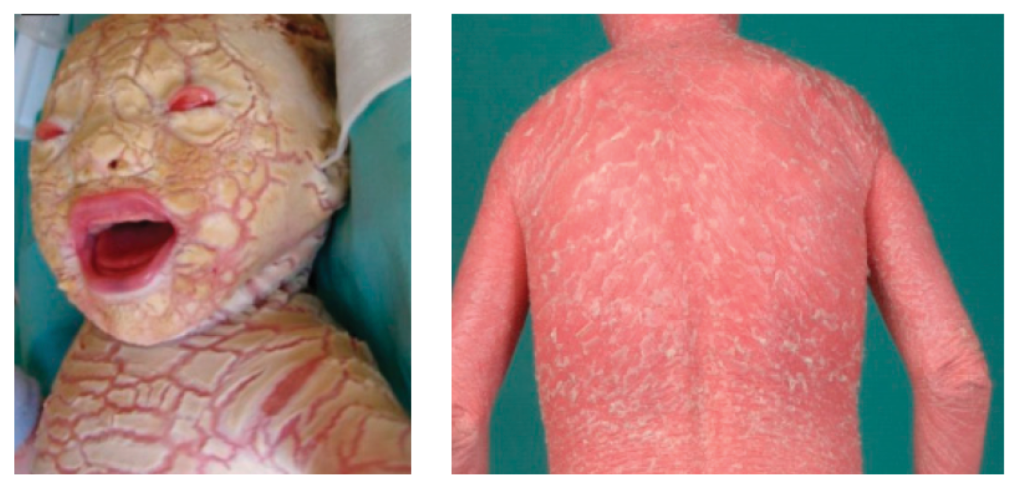

Epidermal differentiation disorders (EDDs) refer to a group of skin conditions that cause a widespread persistent dry, scaly skin. This can range from mild to severe and is sometimes associated with skin inflammation. Generally, EDDs are present from birth and are life-long conditions. Common forms of inherited EDDs are usually mild. Some rare types may also cause problems elsewhere in the body. Several EDDs present with ‘collodion baby’, a shiny film-like covering that is shed several weeks after birth (see figure 1).

Clinical features

Inherited EDDs can present in a range of ways, for example as non-syndromic (nEDD) and syndromic (sEDD)s. Some of these are listed below.

Note: Recently, a dyadic (genotype based) naming of EDDs has been proposed, with the aim of gradually replacing previous terms, such as ichthyoses and palmoplantar keratodermas.

Ichthyosis vulgaris (FLG-nEDD)

This is the most common form of EDD, affecting 1:100 to 1:250 people. It is caused by loss-of-function variants in the FLG (filaggrin) gene. It usually manifests during infancy with dry skin and mild scaling. The scaling is particularly marked on the lower limbs. It is an autosomal semi-dominant condition: when both copies of the gene are affected, then patients typically have a more severe phenotype. It is associated with atopy and keratosis pilaris. Typically, mild presentations would normally not warrant genomic testing.

X-linked recessive ichthyosis (STS-sEDD)

Also known as steroid sulfatase deficiency, X-linked recessive ichthyosis is caused by a pathogenic variant (normally a complete gene deletion) in the STS gene. It can present at or soon after birth with large, thin and translucent scales. These are gradually replaced by firmly adherent polygonal dark scales, particularly on the extremities, trunk and neck.

Collodion membrane at birth

Lamellar ichthyosis (LI) (TGM1-nEDD)

The collodion membrane is replaced by a pattern of large brown scales. This can be a very severe disease with ensuing ectropion, eclabium and/or alopecia, among others. Erythema is not a prominent feature. TGM1 pathogenic variants account for up to 90% of classical LI. However, it is now considered to exist on a spectrum with congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma, which may be caused by a range of genes including NIPAL4, ALOX12B, ALOXE3, ABCA12, PNPLA1, ASPRV1 and CYP4F22.

Harlequin ichthyosis (ABCA12-nEDD)

This extremely severe form of ichthyosis is caused by biallelic pathogenic variants in ABCA12. Babies are born with extremely thickened skin (see figure 1), which results in similar features to severe LI but also ischaemia, autoamputation of digits and significant infant mortality.

Figure 1: Harlequin ichthyosis (ABCA12-nEDD) at birth and later in life

Images reproduced from the publication by Hotz A, Kopp J, Bourrat E and others, under Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY-4.0) license.

Blistering ichthyosis

Epidermolytic ichthyosis (EI) (KRT1-nEDD)

EI is generally caused by an autosomal dominant pathogenic variant in KRT1 or KRT10. It presents at birth with generalised erythema, blisters and peeling skin. As the child ages, the skin fragility decreases but a marked hyperkeratosis develops. This may be cobblestone on extensor surfaces and, when it affects palmoplantar surfaces, it can be so severe that it can causes contractures.

Superficial EI (KRT2-nEDD)

This is a milder form of EI, which may present at birth or later with superficial mild blistering particularly following trauma. Later there may be hyperkeratosis. It is usually caused by an autosomal dominant pathogenic variant in KRT2.

Syndromic ichthyoses

Netherton syndrome (SPINK5-sEDD)

This is a severe congenital ichthyosis caused by pathogenic variants in SPINK5, leading to defective skin barrier function, trichorrhexis invaginata (‘bamboo’ hair) and atopy.

Sjögren-Larsson syndrome (ALDH3A2-sEDD)

This syndrome is due to pathogenic variants in ALDH3A2. It presents with ichthyosis, spastic diplegia or quadriplegia, and intellectual disability.

Genomics

There are many different genetic causes of inherited EDDs. Variable expressivity can occur. Some genetic causes can be associated with additional medical issues. Clinicians should be aware of some additional and specific points, detailed below.

- Ichthyosis vulgaris is caused by variants in the FLG gene, which is semi-dominant in its inheritance pattern. Typically, patients with heterozygous variants have a milder presentation, while homozygous and compound heterozygous have more severe features.

- Variants in the FLG gene are relatively common (1:100 to 1:250) and, as such, there are many reported cases in which FLG variants are co-inherited with other types of ichthyosis, thus contributing to a more severe phenotype.

- X-linked ichthyosis is caused by gene deletions in 90% of cases. In a minority of cases, the deletion also encompasses neighbouring genes, causing additional medical problems such as learning difficulties and behavioural differences.

Diagnosis

Genomic testing should be targeted at those where a genetic or genomic diagnosis will guide management for the proband or family.

Individuals with at least two features from the list below should be considered for genomic testing:

- born with collodion membrane;

- erythroderma;

- dark plate-like scales or fine white scaling;

- ectropium/eclabium; and/or

- hyperkeratosis.

For further information about genomic testing, please see Neonate with scaly skin and thickened palmar skin.

Inheritance and genomic counselling

There are many different genetic causes of inherited EDDs. Inheritance patterns include autosomal dominant, autosomal semi-dominant, autosomal recessive and X-linked. Genomic counselling is essential to discuss inheritance risks and implications for family members.

For autosomal dominant inheritance:

- Individuals affected by an autosomal dominant condition have one working copy of the gene, and one with a pathogenic variant.

- The chance of a child inheriting the gene with the variant from an affected parent is 1 in 2 (50%).

For autosomal semi-dominant inheritance (as seen for the FLG gene):

- Patients with one working copy of the gene have milder symptoms. Patients in which both copies of the gene have causative variants have more severe symptoms.

- Reproductive implications will depend on the specific genotypes of the parents in question. Seek specialist advice from clinical genetics in complex cases.

For autosomal recessive inheritance:

- If both parents are carriers of an autosomal recessive condition, with each pregnancy there is a:

- 1 in 4 (25%) chance of a child inheriting both gene copies with the pathogenic variant and therefore being affected.

- 1 in 2 (50%) chance of a child inheriting one copy of the gene with the pathogenic variant and one normal copy, and therefore being a healthy carrier themselves; and

- 1 in 4 (25%) chance of a child inheriting both normal copies and being neither affected nor a carrier.

For digenic inheritance (where variants in two different genes are involved), which has been observed for the relatively common FLG variants:

- The presence of more than one genetic cause can modify the phenotype, typically resulting in more severe symptoms.

- Reproductive implications will depend on the specific genotypes of the parents in question. You should source specialist advice from clinical genetics in complex cases.

For X-linked recessive inheritance:

- X-linked recessive conditions are usually only present in males.

- Males with X-linked conditions cannot pass on the variant to their sons, but they always pass their affected X chromosome to their daughters. If the condition is recessive, their daughters will be carriers for the condition.

- Female carriers of X-linked recessive conditions have a second working copy of the gene and are therefore usually unaffected, or affected only mildly.

- Sons of female carriers of X-linked recessive conditions have a 1 in 2 (50%) chance of being affected by the condition, and their daughters have a 1 in 2 (50%) chance of being carriers.

Incomplete penetrance can occur when not everyone who has a causative variant develops the disease.

Reproductive options are available if patients are concerned about having an affected child. This can include testing in early pregnancy, or potentially preimplantation genetic diagnosis.

Management

Management focuses on symptomatic treatment. For the milder types of EDD, treatments typically include regular bathing and application of moisturisers. Steroids are not effective in EDDs.

Infants with more severe types of EDD may require intensive dermatolical and nursing care. Children and adults affected by these types may be given a trial of retinoid (synthetic vitamin A) treatment, either in cream or tablet form. Recently, some patients have benefitted from being treated with repurposed biologics developed for other inflammatory skin diseases, such as eczema.

Referral of affected patients to clinical genetics should be considered to discuss onward management, family planning implications and cascade testing of relatives at risk.

Resources

For clinicians

DermNet: Ichthyosis

References:

- Akiyama M, Choate K, Hernández-Martín Á and others. ‘Nonsyndromic epidermal differentiation disorders: a new classification toward pathogenesis-based therapy‘. British Journal of Dermatology 2025: article number ljaf154. DOI: 10.1093/bjd/ljaf154

- Hernández-Martín Á, Paller AS, Sprecher E and others. ‘A proposal for a new pathogenesis-guided classification for inherited epidermal differentiation disorders‘. British Journal of Dermatology 2025: volume 193, issue 3, pages 544–548. DOI: 10.1093/bjd/ljaf065

- Mazereeuw-Hautier K, Paller AS, Dreyfus I and others. ‘Management of congenital ichthyoses: guidelines of care: Part one: 2024 update‘. British Journal of Dermatology 2025: volume 193, issue 1, pages 16–27. DOI: 10.1093/bjd/ljaf076

- Paller AS, Teng J, Mazereeuw-Hautier J and others. ‘Syndromic epidermal differentiation disorders: New classification towards pathogenesis-based therapy.‘ British Journal of Dermatology 2025: article number ljaf123. DOI: 10.1093/bjd/ljaf123

For patients

- British Association of Dermatologists: Ichthyosis

- Ichthyosis Support Group