Hereditary haemochromatosis

Hereditary haemochromatosis is characterised by an excess of iron in the body. It affects all genders equally, though women often present later than men. It is caused by pathogenic variants in the HFE gene.

Overview

Hereditary haemochromatosis (HH) is an autosomal recessive condition characterised by progressive iron overload in the body, leading to multi-organ damage.

Clinical features

Hereditary haemochromatosis typically presents between 30 and 60 years of age. Although all genders are equally likely to have the pathogenic genetic variants that cause HH, clinical features are more commonly seen in males. It is common within northern European populations, especially in those with Celtic heritage. Women tend to present roughly 10 years later than men, and more commonly after menopause.

Early diagnosis is not easy, as many of the symptoms are common and non-specific. They include:

- weakness and lethargy;

- abdominal pain;

- arthralgia (particularly of the metacarpophalangeal joints);

- weight loss; and

- asymptomatic hepatomegaly.

Given the non-specific nature of the early features, it is vital for clinicians to be alert to family history, particularly because early diagnosis directly improves prognosis.

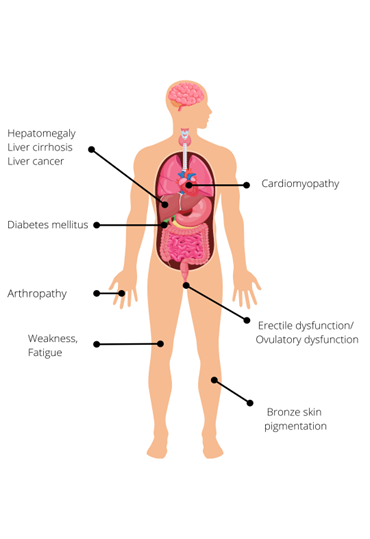

Later features of HH, which are caused by excessive parenchymal storage of iron in target organs, include:

- increased skin pigmentation (bronzing);

- diabetes mellitus;

- cardiomyopathy;

- hypogonadism, leading to decreased libido, impotence, infertility or premature menopause; and

- liver manifestations:

- hepatomegaly;

- cirrhosis; and

- hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma, which are responsible for one third of HH-related deaths.

Figure 1: Clinical features of hereditary haemochromatosis

Due to the loss of iron during menstruation, women are less likely than men to develop clinical features of iron overload . If HH is diagnosed before the development of cirrhosis or diabetes mellitus, and treated adequately by venesection, life expectancy can be normal. However, if the diagnosis is made after the onset of irreversible organ damage, life expectancy is significantly reduced, primarily due to the risk of liver cancer.

Genetics

HH is caused by pathogenic variants in the HFE gene. HFE is strongly expressed by liver macrophages and intestinal crypt cells and plays a key role in iron homeostasis. Pathogenic variants in this gene interfere with this homeostasis, leading to inappropriately high iron absorption by the intestinal mucosa.

There are two common pathogenic variants that can cause HH: C282Y (p.Cys282Tyr) and H63D (p.His63Asp). Around 90% of patients with clinical HH are homozygous for C282Y (both their copies of the HFE gene have this variant), as this genotype is most at risk for iron overload. Individuals with one C282Y and one H63D pathogenic variant (compound heterozygotes) may accumulate iron, but the risk of developing clinical HH is much lower than that of C282Y homozygotes. H63D homozygotes are also far less likely to have clinical features.

Figure 2: The most common genotypes for hereditary haemochromatosis with reported allele frequencies

Key: Red = C282Y variant. Blue = H63D variant. Green = normal gene.

Penetrance for HH is incomplete and the condition shows variable disease expression. This means that many individuals with HH may never manifest serious clinical features. Clinical penetrance (the proportion of individuals who develop clinical features) is much less common than biochemical penetrance (the proportion of individuals with increased transferrin saturation and serum ferritin concentration but no clinical features). For this reason, population screening for the HFE genotype is not recommended.

HH is a genetically heterogeneous condition, which means that it can be caused by pathogenic variants in other genes, although this is much rarer.

Inheritance and genomic counselling

HH is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. The parents of most affected individuals are carriers for the condition, so they have a 25% (one-in-four) chance of having another affected child.

For this reason, it is important to clarify the genetic status of adult siblings and offspring of affected individuals, in order to allow prompt initiation of treatment and preventative measures. Since the condition does not manifest before adulthood, testing children is unlikely to be valuable (juvenile HH is a separate, rarer, more severe condition, with a different genetic basis. Families with HH are not generally at risk of juvenile-onset disease).

Increasingly, genomic testing for HH is being managed in primary care, with regional support from haematology services or, occasionally, clinical genetics services.

Management

- Treatment of biochemical iron overload via venesection is indicated for all fit patients, with or without clinical features. The frequency of venesections may be individualised depending on the severity of symptoms, age, comorbidities and tolerability of the procedure.

- Where relevant, patients with HH should be advised to reduce dietary iron intake, such as avoiding excess red meat, multivitamins containing iron, fortified cereals and similar.

For more information, see Presentation: Patient with iron overload (suspected hereditary haemochromatosis).

Resources

For clinicians

- GeneReviews: HFE hemochromatosis

- NHS England: National Genomic Test Directory

References:

- Drakesmith H, Sweetland E, Schimanski L and others. ‘The hemochromatosis protein HFE inhibits iron export from macrophages’. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2002: volume 99, issue 24, pages 15,602–15,607

- Firth HV, Hurst JA, Hall, JG. ‘Oxford Desk Reference: Clinical Genetics and Genomics’. Oxford University Press 2017: pages 335–540. DOI: 10.1093/med/9780199557509.003.0003

- Fitzsimons EJ, Cullis JO, Thomas DW, Tsochatzis and others. ‘Diagnosis and therapy of genetic haemochromatosis’. British Journal of Haematology, volume 181, issue 3, pages 293–303. DOI: 1111/bjh.15164

- Pilling LC, Tamosauskaite J, Jones G and others. ‘Common conditions associated with hereditary haemochromatosis genetic variants: Cohort study in UK Biobank’. British Medical Journal 2019: volume 364. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.k5222

For patients

- NHS Health A to Z: Haemochromatosis: Symptoms

- British Heart Foundation: What is haemochromatosis?

- Haemochromatosis UK: What is genetic haemochromatosis?