Frontotemporal dementia

Frontotemporal dementia is an uncommon dementia subtype in which a genetic diagnosis should be sought.

Overview

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is both a clinical and pathologically heterogenous condition that is characterised by changes in behaviour, personality, language and motor function. Though rare, it is a relatively common cause of early-onset dementia and inherited dementia. Most genetic forms of the condition are accounted for by variants in three dominantly inherited genes (C9orf72, GRN and MAPT).

Clinical features

The typical age of onset of FTD is around 58 years. Onset before 40 or after 75 years is reported but relatively unusual.

Clinically, FTD can divided into subtypes based on the predominant symptoms at presentation.

Behavioural variant FTD (bvFTD)

bvFTD is the most common subtype, accounting for about half of all FTD cases and most likely to have a genetic basis.

The main clinical hallmark is a progressive change in personality and behaviour, which can include disinhibition, apathy or loss of empathy, hyperorality and dietary changes, and/or compulsive behaviours. Patients often lack insight into these changes, and so they are more often reported by family members.

There may be few or no neurological signs at presentation, though frontal release signs (such as the palmar grasp and palmomental reflex) can be seen.

Primary progressive aphasia (PPA)

PPA is characterised by progressive language disturbance, with relative preservation of other cognitive domains.

Three major variants are described:

- Non-fluent variant PPA (nfPPA): effortful, halting speech with speech-sound errors and agrammatism.

- Semantic variant PPA: impaired single word comprehension and object naming, with preserved fluency.

- Logopenic variant PPA: slow speech, with frequent word-finding difficulties, though normal single word comprehension and articulation. Often speech lacks detail and is vague.

Only nfPPA and semantic variant PPA are commonly associated with FTD pathology, with logopenic variant PPA typically associated with Alzheimer’s pathology.

FTD with associated motor symptoms

Most patients with bvFTD or PPA do not have prominent motor symptoms early in the disease course. Those that do, or where they develop over the course of the condition, usually present as motor neurone disease (MND) or atypical Parkinsonism.

- MND with FTD (FTD-MND):

- Typical of ‘classic’ MND, with a mixture of upper and lower motor neuron signs. Bulbar involvement, pseudobulbar affect and psychotic symptoms more commonly seen in FTD-MND.

- A genetic cause, usually c9orf72 repeat expansion, is common in this group of patients.

- Atypical Parkinsonism:

- Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) typically presents as a relatively symmetric extrapyramidal syndrome, with marked axial rigidity, falls and abnormal saccadic eye movements. Most patients have cognitive changes that overlap with the features of bvFTD. Single gene causes of PSP are rare but where it presents in someone with FTD, a MAPT variant is more likely to be identified.

- Corticobasal syndrome (CBS) typically presents as an asymmetric extrapyramidal syndrome with limb rigidity, dystonia and coarse tremor, as well as falls and postural instability. Cortical dysfunction is prominent, which can include cognitive impairment, behavioural change, cortical sensory loss, limb apraxia and alien limb phenomenon. Association with a genetic cause is rare but may be seen in patients with GRN variants.

Neuropathology

Frontotemporal lobe degeneration (FTLD) is an umbrella term that refers to the neuropathological findings in patients with FTD and is subdivided based on the nature of the protein inclusions found at autopsy. Over 90% of patients with FTD are found to have one of two major categories of protein inclusion, either tau protein or TAR DNA-binding protein 43 kDa (TDP43).

It should be noted that each FTLD neuropathology can be associated with more than one clinical syndrome (see below), and that each clinical syndrome can be associated with different FTLD subtypes. There are some strong associations; for example, more than 90% of patients with FTD-MND have TDP43 pathology.

Genomics

FTD is highly heritable, with a significant proportion of patients with FTD having a relative with dementia. A family history of FTD may not be available due to the nature of the illness, age of affected family members and inconsistency in diagnostic handles in prior generations. If a family history is present, it is often said to be an unspecified dementia rather than FTD. Family history of young-onset Parkinsonism or motor neuron disease (any age) are important clues, which may not be disclosed without direct questions. As such, genomic testing should be considered even in the absence of a family history.

A family history suggestive of autosomal dominant inheritance may be evident in up to one-quarter of affected patients. Those with a positive family history are said to have familial FTD (fFTD). Although genomic testing is more likely to be fruitful in this group, it should be considered in all patients with this clinical diagnosis. Where a single-gene disorder is identified, the majority are associated with variants in three genes; C9orf72, MAPT and GRN (table 1).

Testing is available through whole genome sequencing (WGS) and short tandem repeat testing (STR) for a panel of genes associated with adult onset neurodegenerative disorders. Variants in a number of other genes associated with FTD are infrequently recognised and individually rare.

| Gene | Inheritance | Genetic features | FTLD pathology | Clinical features |

| C9orf72 |

|

|

TDP-43 |

|

| GRN |

|

~90% penetrant by 75 years of age. | TDP-43 |

|

| MAPT |

|

Fully penetrant | Tau |

|

Table 1: Familial FTD: most commonly involved genes

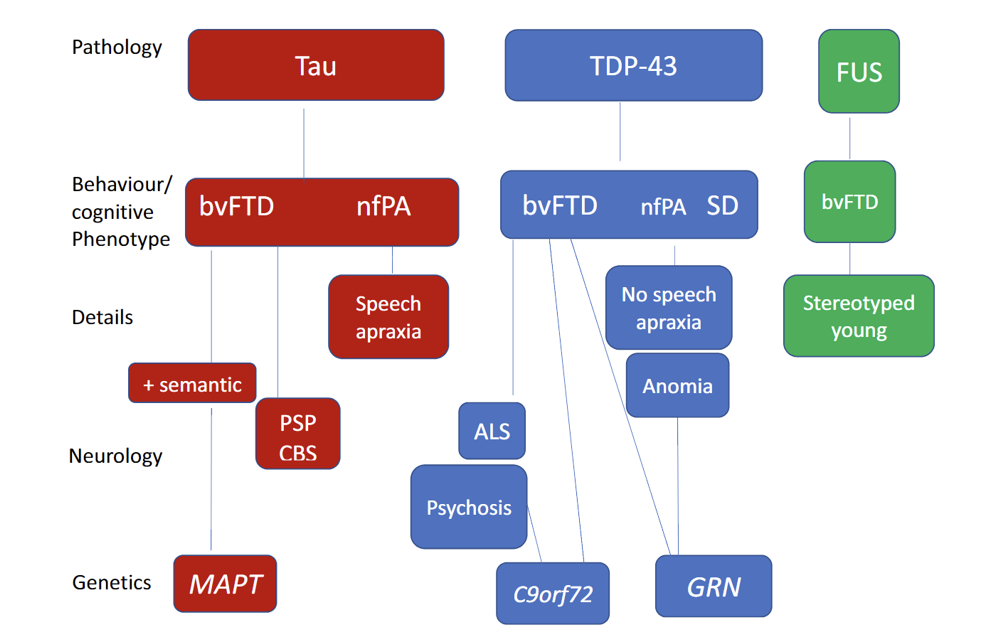

Figure 1: The relationship between the clinical, pathological and genetic associations in the main subtypes of FTD

Abbreviations: FUS = fused-in sarcoma; nfPA = non fluent progressive aphasia; SD = semantic dementia; CDS = corticobasilar syndrome.

Diagram from: Snowden JS. ‘Changing perspectives on frontotemporal dementia: A review‘. Journal of Neuropsychology 2023: volume 17, issue 2, pages 211–234. DOI: 10.1111/jnp.12297. Licensed under Creative Commons, available for open access use.

Inheritance and genomic counselling

Most genetic variants associated with FTD follow an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. As such, affected individuals have a 1-in-2 (50%) chance of passing the variant onto any children they may have.

Penetrance depends on the underlying variant and can be highly variable with regards to clinical phenotype, age of onset and progression.

Identifying a genomic cause of dementia within a family can have a profound effect. For example, it may influence the decisions that at-risk family members make about their future care, finances or family planning. Predictive (presymptomatic) testing is possible for at-risk relatives once a particular pathogenic variant has been identified. At-risk relatives should be offered referral to local clinical genetics services to discuss predictive testing.

Management

There is currently no cure or disease-modifying therapy for FTD. Management is focused on maximising quality of life, support for carers and promoting independence. Therefore, following a diagnosis, or where one is suspected, patients with FTD should be managed by a dementia MDT service. This often includes neurologists, mental health service teams, physiotherapists, speech and language therapists, occupational therapists, psychologists and social workers. Input or advice should be sought from the local clinical genetics service for those with known genetic findings or a strong family history.

There is currently limited evidence for the use of pharmacological treatments in FTD targeted at cognitive or behavioural symptoms, and often side effects preclude their use. Any potential pharmacological treatments are best guided by specialist clinical teams.

Experimental treatments are currently being investigated, including genetic therapies for those with known genetic variants, as well as drugs targeting tau aggregation. Referral to specialist dementia services for those with rare dementia syndromes is highly recommended.

Resources

For clinicians

- GeneReviews: C9orf72 Frontotemporal Dementia

- GeneReviews: GRN Frontotemporal Dementia

- GeneReviews: MAPT-related Frontotemporal Dementia

- NHS England: National Genomic Test Directory

- Royal College of Psychiatrists: The role of genetic testing in mental health settings

References:

- Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S and others. ‘Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants‘. Neurology 2011: volume 76, issue 11, pages 1,006–1014. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821103e6

- Racovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D and others. ‘Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia‘. Brain 2011: volume 134, issue 9, pages 2,456–2,477. DOI: 10.1093/brain/awr179

- Snowden JS. ‘Changing perspectives on frontotemporal dementia: A review‘. Journal of Neuropsychology 2023: volume 17, issue 2, pages 211–234. DOI: 10.1111/jnp.12297

For patients

- Alzheimer’s Society: Young-onset dementia

- The Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration

- Dementia UK: Understanding FTD

- NHS Health A-Z: Frontotemporal Dementia

- Rare Dementia Support: Frontotemporal dementia (FTD)

- Young Dementia Network