Novel ‘virotherapy’ shows promise for skin cancer treatment

Modified virus known as T-vec mounts dual attack on cancer cells

New research has shown that a genetically modified version of the herpes simplex virus could dramatically improve survival rates among some patients with advanced melanoma. This form of skin cancer is the sixth most common in the UK.

Researchers have reported results in the Journal of Clinical Oncology from an international randomised trial involving over 400 patients with inoperable malignant melanoma in the UK, US, Canada and South Africa. Patients received an experimental form of cancer immunotherapy using a modified form of virus called Talimogene laherparepvec – T‑vec for short.

A two-pronged attack on cancer via genetic engineering

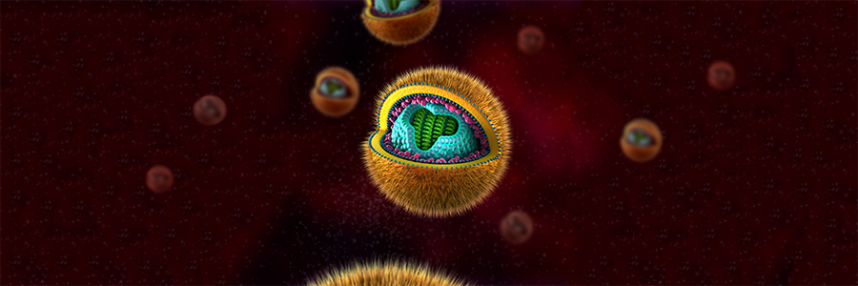

T‑vec has had two non-essential viral genes removed. The removal of these genes suppresses the ability of the virus to cause disease, ensures the virus only replicates in tumour cells and does not evade the anti-tumour immune response.

On top of this cancer-cell specificity, T‑vec includes another modification, insertion of the gene for human granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), expression of which enhances active immune responses against infected host cells.

This new form of ‘virotherapy’ for cancer therefore cleverly combines two distinct approaches, to both selectively replicate inside tumour cells and induce the host immune system to target and destroy these cells.

Understanding patient responses

Patients in the Phase III clinical trial received either T‑vec (stage III and early stage IV disease) or a control form of immunotherapy (stage III disease only). Over 16% of those who received T‑vec showed a treatment response lasting six months or more, compared with just over 2% of those who received the control immunotherapy – a significant difference.

On average, the T‑vec patients survived for 41 months, almost twice as long as the control patient average of 21.5 months; some T-vec recipients showed responses lasting more than three years.

A first line of attack?

The first major clinical trial of virotherapy for skin cancer has therefore shown promising results. One important observation was that patients with earlier stage disease and those who had not received any prior treatment showed the most dramatic responses, suggesting that T‑vec may be a suitable first-line treatment for metastatic melanoma where surgical removal is not an option. Ongoing trials will investigate this.

Researchers also need to discover why some patients respond to T‑vec while others do not – this could relate to the precise genetic features of their tumours, potentially requiring a form of companion diagnostic genomic testing to identify those who can really benefit.

–